The shrill sound of the bell fills the classroom, signalling the end of class. The scuffle of backpacks zipping closed and students pushing in their chairs underlies the sound of rising chatter as I prepare to head to my next class.

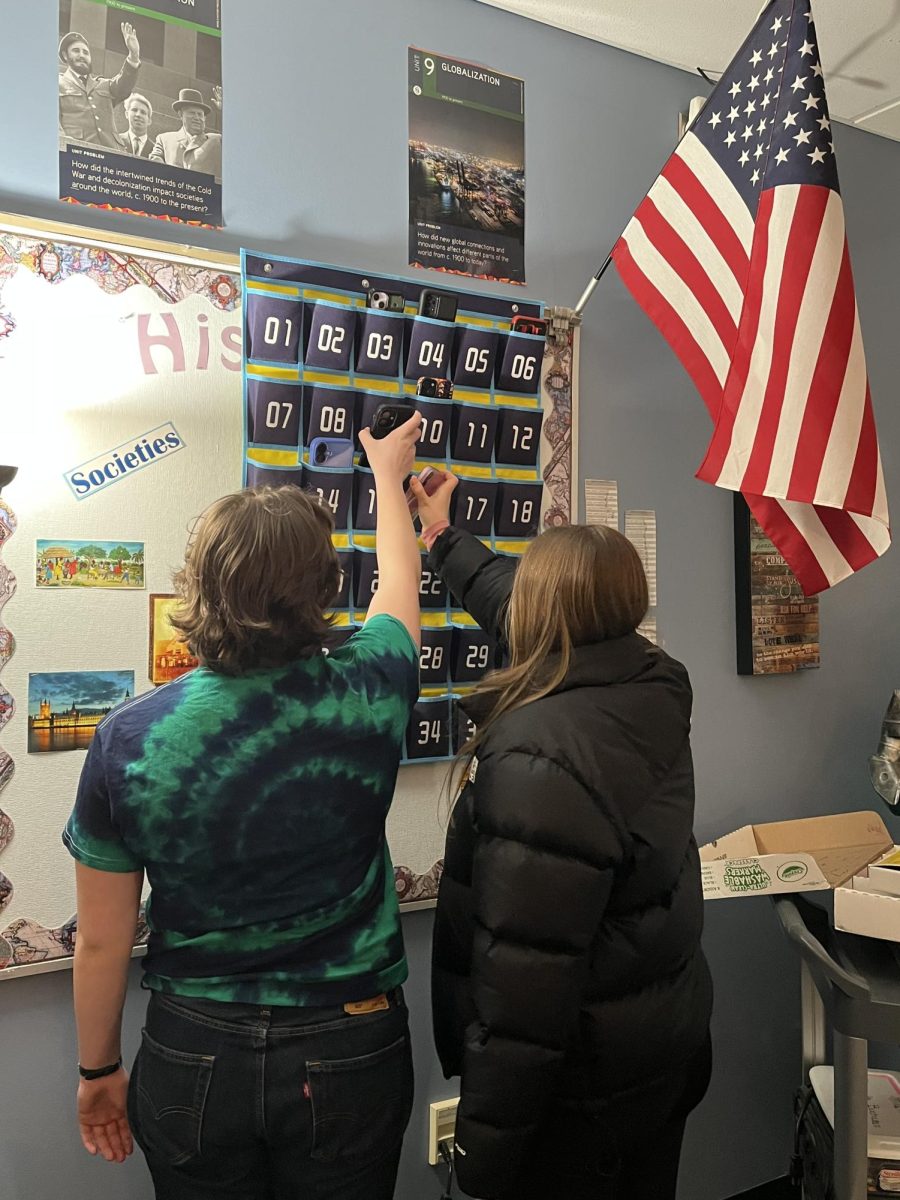

Before I make my way to the door, though, I make a beeline for the back corner of the classroom, joining a throng of students clustered around a rectangular tapestry hanging from the wall. Shuffling through the crowd, I snatch my phone from one of the pockets on the cell phone pocket holder and immediately check my notifications.

As a teenager, it can be hard to ignore the urge to check Snapchat or Instagram between classes. There is no denying that we live in an increasingly digital world, a world where the idea of a “TikTok ban” sends waves through both the government and society, and Instagram trends shape our popular styles. For adolescents and even young children, our phones represent more than just a communication device and a means of accessing information; they are the vehicle through which we express ourselves and connect with others, forging a path of digital globalization and interconnection that even youth can participate in.

For students in Michigan, though, this could very well change soon. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer recently called for Michigan’s Congress to pass bipartisan legislation restricting cell phone use in class.

“It’s hard to teach geography or geometry when you’re competing against memes or DMs,” Whitmer said in her State of the State address on February 26, 2025. She went on to cite youth mental health and a lack of participation in class as justification for the legislation.

Whitmer isn’t the first lawmaker to push for cell phone restrictions in schools. Eight other states from across party lines have implemented legislation either limiting cell phone usage in public schools or banning it altogether, and thousands of school districts across the country have done so independently, with 83% of National Education Association members supporting full-day bans on cell phones in the classroom. Michigan Rep. Mark Tisdel unsuccessfully proposed a bill banning cell phones in classrooms in 2024, though Whitmer’s push to revisit the issue could result in new legislation.

While Whitmer’s concerns about mental health and academic performance are understandable, they misrepresent cell phones as a superficial device that serves as little more than a distraction. Many scoff at the view of cell phones as “essential,” but the simple truth is that they are. We live in a day and age when communication is vital, and cell phones provide this link.

Less than five years ago, four students were killed in a school shooting at Oxford High School in Oxford County, Michigan, just an hour away from Brighton. This incident echoes dozens of other violent events that have occurred in schools over the past two decades. With mass shootings in school settings growing more prevalent in recent years, having communication ties to parents and adults is more important than ever. Many models that focus on banning phone use in classrooms, though, require students to turn in their phones to school authorities or store them in their backpacks or lockers. In the event of an emergency, this could easily sever the communication link between students and their parents. Many adults share this concern, with only 36% of parents of K-12 students supporting full-day bans on cell phones in the classroom.

It is easy to understand why administrators and teachers support restrictions on cell phone use in the classroom. With members of Generation Z already spending an average of six to eight hours on screens each day, it’s hard to deny that the popularity of cell phones has quickly morphed into an addiction epidemic. Understandably, many teachers want to minimize distractions in learning environments and promote face-to-face social interactions among their students. Some research also suggests that allowing students to use cell phones in the classroom can inhibit academic performance and even cause them to lose up to a week of instruction.

While banning cell phones in schools may contribute to small gains in student performance, however, it ultimately fails to address the bigger picture. Schools should be focused not on restricting cell phone use further but tackling the root cause of cell phone and social media addiction. The “cell phone pockets” Brighton High School has introduced have done nothing to address why students are so hooked to their phones in the first place. If schools invested more resources into educating students about social media addiction and promoting alternative activities to get them off of screens, cell phone bans may not even be necessary. Some schools, like the San Ramon Valley Unified School District in Contra Costa Valley, California, have recognized the issue of screen addiction and taken certain measures to fight it. Beyond just offering students lessons on digital citizenship, the district has promoted an approach that emphasizes “when it’s important to put [technology] down.” The schools have provided both students and parents with education and resources about the correct time and place to use social media, encouraging students to set their own limits and offering support to those who are struggling.

However, the unfortunate reality is that programs like this are few and far between. Gov. Whitmer’s approach surrounding cell phone restrictions in the classroom only signifies the growth of policies focused on regulation instead of education, and social media education programs already in place often emphasize digital citizenship and cyber safety rather than screen addiction. Students may have the tools to navigate social media and the Internet safely, but they lack the ability to cope with why they are so attached to their devices in the first place.

For better or worse, cell phones and social media have cemented themselves as crucial components in people’s lives, especially for children and students. Simply forcing students to relinquish them at school not only poses dangerous implications in the event of an emergency but also fails to consider the broader issue of screen addiction. If legislators and educators hope to minimize the influence cell phones play in the classroom, banning them isn’t the right move. Fighting the screen epidemic is going to require more innovative solutions, solutions that tackle the problem from the ground up.

When the bell rings at the end of class, it’s not our phones that should be missing—it’s the urge to check them in the first place.